Imagining more in NDIS home and living options

Key points

What should the goal be

- Creation of an authentic sense of home on the same basis as for non-disabled people to enable Australians living with disability to take up ordinary valued roles in community life

How to achieve this goal

- NDIA stops funding group houses and, instead, invests in choice-driven individual home and living options that align with Scheme values

- NDIA stops defining group houses according to a specific number of bedrooms or residents and, instead, recognises that it is the lack of choice and the character and operations of group houses that sets them apart from ordinary homes

- NDIA ensures plan budgets are always individualised and not arbitrarily tied to group purchasing requirements

- NDIA recognises that there is an array of alternatives to group houses and these do not always cost more

- NDIA removes perverse incentives from funding models and, instead, ensures they are designed to enable outcomes that are consistent with Scheme values

- SDA and SIL providers are required to adopt and implement practices that align with Scheme values

‘Few Australians without a disability can imagine what it would be like to have no say in where they live or who they live with. The freedom to choose where and with whom one lives is a fundamental freedom, but it is one few people with disabilities are able to exercise. Many people with disabilities want to live independently in the community but are unable to access the support they need to do so.’

This quote from the landmark ‘Shut Out’ report released in 2009 tells of the frustrations Australians living with disability experienced before the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) was established. With little support available, most were unable to access independent living options of their choice, forcing them to continue living in the family home well into adulthood or find themselves stuck in inappropriate congregated living facilities usually operated by state and territory governments. Such facilities resulted in segregation, discrimination, and exclusion, as well as severely restricting opportunities for people living with disability to take up valued roles in community life. Residents were ‘shut out’ of ordinary life in their neighbourhoods and local communities.

Yet, 10 years on from the creation of the Scheme, little has changed. In fact, the National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA) has admitted that in 2020 more people entered congregate forced shared living arrangements than exited, despite billions of dollars being spent through the Scheme. As the type of NDIS funding that pays for staff support, Supported Independent Living (SIL) budgets give an insight into the prevalence of people living with disability being forced to live under these arrangements. Currently, there are just under 30,000 NDIS participants with SIL funding in their plans.

In this fifth paper in our NDIS Review Conversation Series, we focus on the need to revitalise the Scheme’s values of individual choice and control in relation to housing and daily living supports. We identify what makes an authentic home and how the NDIA’s continued funding of ‘group houses’ where people have not chosen to live together fails to achieve this. We deliberately use the term ‘group houses’ rather than the more common ‘group homes’ because, as this paper will demonstrate, the use of ‘home’ in this context is a misnomer, and the use of the word ‘home’ in the phrase ‘group home’ profoundly compromises its true meaning. Group houses are akin to service facilities where staff are front and centre and people living with disability are congregated, disempowered, and segregated from their communities. Moreover, living in such a facility does not fulfill the promise of the NDIS to enable all Australians to enjoy ordinary good lives.

Creating an authentic sense of home

Home is a place of comfort, rest, renewal, and belonging; where we are free to be ourselves, personalise our surroundings, and make decisions about who enters and on what terms. Home is the foundation that allows us to live ordinary good lives, pursue our goals and interests, do things that give us meaning and purpose, build and maintain relationships with friends and loved ones, and connect with our neighbours and the life of our local communities. And home is where we find a sense of safety, security, and certainty when we return at the end of our day. Home enables choice and control in our lives; upholds our individuality, self-determination, and status; and facilitates the use of our existing skills and the development of new ones.

To invest in the chances of an authentic sense of home, the dwelling should be accessible in line with a person’s individual requirements and close to ordinary community resources, such as shops, health services, transport hubs, recreation facilities, and other public amenities. The resident/s should be in charge of what happens in the home. Appropriate assistive technologies should be utilised to meet the occupant’s circumstances and preferences, to maximise personal control. Crucially, a home should be a place where a person can welcome family, friends, and visitors and build ordinary valued relationships with their neighbours. When the above elements are accomplished, a person is much more likely to take up valued roles in community life, with all the meaning, belonging, and natural safeguarding this brings.

The way in which home and living supports are provided under the NDIS is critically important to fulfilling the principles and purpose of the Scheme, particularly those of participant choice and control and social and economic participation.

When ‘home’ is, in reality, a facility

Unfortunately, the NDIS has continued to fund group houses, where people are coerced to share their living space with other people also living with disability. In its character and effect, this is a service facility, not a home. These facilities are not anchored on deep familial or personal connections, but on imagined compatibility based on superficially similar support needs, outdated economics of disability support, and/or a scarcity of accessible ordinary housing. None of these ‘justifications’ are acceptable. They are not consistent with proclaimed Scheme values and would not be acceptable to non-disabled Australians, so why should they be acceptable for a person living with disability? The NDIS will not achieve its intended purpose unless it delivers housing and daily living supports in ways that create an authentic sense of home for each person.

Much has been voiced or written elsewhere about the nature of group houses, including some views that group houses can be considered good if there is quality in the care and if the residents chose it. We do not intend to navigate the detailed points therein within this paper. Instead, we assert the group house model must be rejected because it is not an option chosen by most Australians in their own lives. There may be times, for example when young people first leave home, or go to full-time adult study, where they may be sharing with several other people in similar circumstances. But beyond instances where a household might have several adult family members, it is rare for a group of non-related adults to share a dwelling long term. The group house is not a choice most Australians make. Therefore, it is unacceptable to suggest it is suitable for Australians living with disability, let alone for it to have become their default housing option if they do not have the resources to make their own arrangements.

Further, the nature of a group house works against the goal of inclusion. When several people living with disability are placed in a house together, with staff comings and goings, it presents that house not as an ordinary home but as a service venue, a facility, and that changes the way the neighbours and others view the nature of any role they might have in the occupants’ lives. In short, it makes things weird. Also, the economics and habits of group houses mean a participant does not have control because this power is typically held by the paid staff, and they do not have choice because if there are four people living in the house who all want to do to something different, and only one or two staff there to support them, it is going to be impossible for each person to have their choice met.

Home is more than just a house, and it is certainly not a facility. Group houses, even assuming the best of intentions are held, perpetuate segregation and marginalisation. Even with the best of support staff, the group house model is tough going, making it much harder to build momentum for authentic inclusion. Group houses do not have a good track record of delivering authentic choice and control to occupants or enabling people into authentic ordinary social and economic participation. They fail the test for the values the NDIS is meant to advance and uphold.

Regrettably, group houses also do much worse. We have heard from numerous NDIS participants about how they are pressured or forced to live with ill-matched housemates, including situations where they have been subjected to violence as a result. The NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission’s ‘Own Motion Inquiry into Aspects of Supported Accommodation’ report released in January highlighted the shocking prevalence of reportable incidents occurring in group houses, with the inquiry investigating about 7,000 incidents and complaints related to the facilities of seven providers during a period of about four years. The incidents include abuse, neglect, and unlawful physical or sexual contact.

The fork in the road

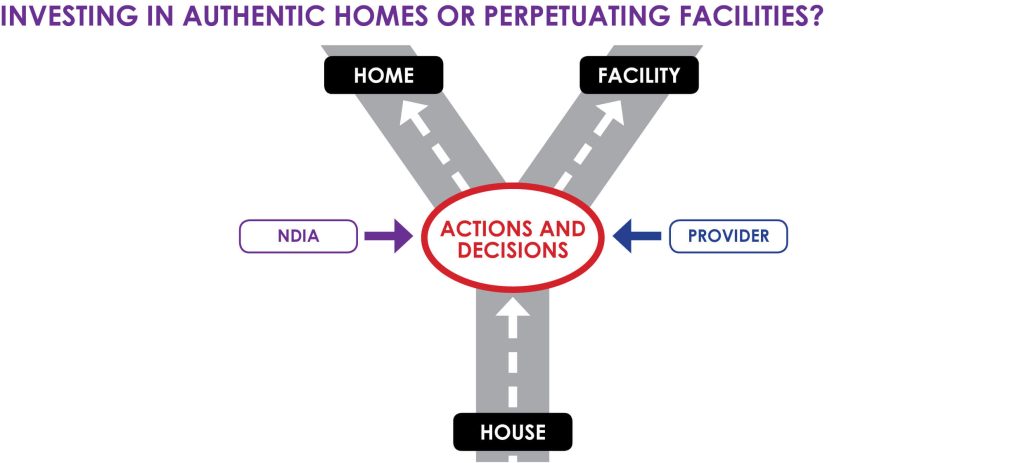

The NDIA and providers of NDIS housing and daily living supports, including state and territory governments, play a significant role in enabling or undermining an authentic sense of home for participants. When a house is made available, it will either provide an authentic sense of home, or become a facility. There is no middle ground, there is no ‘sitting on the fence’. Each and every decision made by the NDIA as funder, and by any support providers involved, will either advance and reinforce an ordinary sense of home, or advance and reinforce a sense of service facility.

Most Australians are themselves the primary agents for how they create a personal sense of home in the house they live in. And so it should be for Australians living with disability. However, they have other agents in their life, most notably the NDIA and support providers, and the significance of their actions and decisions in determining whether a house will become a home, or a facility, cannot be overstated. Every decision made, every action taken, is from a fork in the road, where one way leads to a rich sense of ordinary home life, and the other way leads to a facility.

The commitments Australia currently fails to uphold through the NDIS

As a signatory to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD), Australia has an obligation to ensure that citizens living with disability have the right to ‘choose their place of residence and where and with whom they live on an equal basis with others and are not obliged to live in a particular living arrangement’. All tiers of government have also committed in Australia’s Disability Strategy 2021-2031 to ensure that ‘housing is accessible and people with disability have choice and control about where they live, who they live with, and who comes into their home’. In its consultation about a new NDIS Home and Living Policy, the NDIA has itself acknowledged the discrepancy between Scheme values and Australia’s international obligations, on the one hand, and its current practice of perpetuating forced group living, on the other. However, this rhetoric has not yet led to a substantive change in approach.

‘Group houses’ and quasi-block funded SIL undermine Scheme values

The proclaimed values of the NDIS in relation to participant choice and control should rightly mean each participant has a genuine individual choice about where and with whom they live, and how they receive supports. However, the NDIS currently funds a large number of arrangements where the participant was not afforded an authentic choice. If a person did not choose the group living arrangement in which they find themselves, then it is extremely unlikely that they will feel any authentic sense of home or belonging in the place where they reside. Indeed, when alternative options are genuinely available, people living with disability are very unlikely to choose to live in a group house with numerous other housemates not of their choosing for years or even decades of their lives.

The NDIA is replete with good people who readily acknowledge the discrepancy between the inclusion-driven principles and purpose of the NDIS and the continued funding of a fundamentally flawed model of home and living supports that appears to be delivering a new generation of institutionalised group houses that could take decades to unwind. This is particularly evident in the parameters set for NDIS Specialist Disability Accommodation (SDA), a framework designed to stimulate the supply of houses for NDIS participants with higher support needs. Given their higher support needs, their right to choose where and with whom they live ought be particularly well-safeguarded. However, the opposite appears to be the case. In its current review of SDA pricing arrangements, which is the first comprehensive examination of the assumptions and methodologies underpinning SDA since its inception, the NDIA has benchmarked SDA support as a three-person, quasi-block-funded, forced shared housing arrangement. The current SDA model does not include a funding level for a house for one person to live in. Overall, the model incentivises having multiple residents in a property to generate greater financial returns because SDA providers are paid for each resident resulting in a higher total.

The NDIA defines what it calls ‘group homes’ as ‘houses that have 4 or 5 bedrooms’. It is acting to reduce the size of group houses to no more than five residents. However, as argued earlier in this paper, it is the nature of the arrangement and its context, not the number of bedrooms or residents, that determines whether a house is a group house. Reducing or restricting the number of people compelled to live together in one facility will never address the fundamental inconsistency between this approach and proclaimed Scheme values. There is little difference in the experience of being forced to live with four strangers compared to five strangers, or, indeed, two, three, or any other number of people a person does not know. Instead, the critical imperative is for the NDIA to enshrine genuine individual choice and ensure that an authentic sense of home is achieved, not to set a maximum number of other residents that a person can be forced to live and share with.

The NDIA is in similar values strife through the continued use of a funding pathway termed Supported Independent Living (SIL), which funds the supports that take place in a person’s home. SIL is largely predicated on NDIS participants living with other participants and the presence of a SIL budget in a plan likely has a high correlation with having an SDA budget; if an NDIS participant is in an SDA property, they are likely to be the recipient of SIL-funded shared supports. And it is widely known that SIL funding is inflationary and is contributing to the rising cost of the NDIS. In effect, this means the current NDIS SDA framework is inadvertently having an adverse impact on NDIS outcomes and sustainability.

SIL seems to be tethered to pre-NDIS, block-funded models even after almost 10 years of NDIS operations. SIL supports are commonly treated as a shared group purchase of all the people living in a group house without any real say for the individual participant about whether they want to share or who the shared support should be provided by. Often SIL staff manage group houses as institutionalised facilities, where the participant experience of choice is superficial and where the rhythms of daily life are more geared to the limitations of staff rosters and staff practice preferences. Living under these conditions heavily inhibits the creation of any sense of home, belonging, or personal authority. Recently, some SIL providers have adopted ‘committee governance’ approaches, whereby residents or their nominated informal supporter meet regularly to decide how the ‘group house’ operates. Contrary to descriptions of this as an ‘innovative’ approach, it remains far removed from how life in an ordinary home usually occurs, especially in relation to the degree of power and influence the non-occupants (the staff) have in such discussions. Again, it is critical the NDIS adheres to the principles of personalised budgeting and genuinely embeds and safeguards authentic individual choice and control in the selection of support providers and how supports are delivered.

Importantly, we are not suggesting that personalised budgets or living alone guarantee individual choice and control or the development of an authentic sense of home. Single resident dwellings with one-to-one supports can also resemble facilities in their character and operations, sometimes with the same extreme and tragic consequences as can happen in group houses. Rather, we argue there needs to be both changes to the structure of NDIS funding to enable genuine individual choice and control, and to the attitudes and practices at the core of delivering housing and home-based supports, to ensure Scheme values are fully realised for each participant. Participant plans should advance and uphold the right to choose where and with whom a person lives, as well as how they receive daily living support, including through the provision of a sufficient budget to implement their reasonable choices. Providers of NDIS housing and daily living supports must place the person at the centre of everything they do, ensuring there is genuine personalisation and an authentic sense of home is created. Importantly, the housing provider must not also be the support provider for the person, as this gives far too much power to that agency and further complicates the vested interest already present.

None of this is new to the NDIA leadership, who have initiated sincere efforts to craft a more values-coherent home and living policy, albeit with the risk the pace of this may currently slow to await the outcome of the NDIS Review. The principal challenge is how best the NDIA leadership draws the line in the sand to ensure new group houses and supports will no longer be funded and every effort is made to make alternative choices available to current group house residents.

Creating new housing options that uphold Scheme values

Eliminating large and small scale, institutionalised, forced shared living for Australians living with disability must be a key imperative of the NDIA and a significant focus of the current NDIS Review’s recommendations. As a first step, the NDIA must stop funding new ‘group houses’ immediately. It should also work with the sector to co-design strategies to transition away from legacy facilities and group houses (see Endnote). To facilitate this, it is essential a new SDA funding model is developed to underpin change and remove the perverse financial incentives that perpetuate forced shared living arrangements. Alongside these steps, it should proactively engage residents of existing group houses in conversations about their housing goals as part of the participant planning pathway. As the aforementioned NDIS Commission report highlighted, these types of conversations with participants are not yet occurring in the form and to the extent needed:

‘There has been limited engagement with those people who have transitioned to the NDIS from state and territory funding arrangements about options for more contemporary living arrangements within the NDIS, should people wish to explore these. This is mainly left to their current providers to facilitate on an individual or house by house basis, and almost always limited to the options that the current providers might have available.’

The NDIA should also increase the momentum of the NDIS element termed Independent Living Options (ILO), which we consider a catch-all concept to describe any and all home and living arrangements that are choice-driven, not group living, and which advance an authentic sense of home. For the sake of Scheme outcomes and accountability, there needs to be a substantial and sustained investment in building ILO momentum, especially through assisting participants and their families to ‘unlearn’ the expectation that ‘if you are not at home with your family, you will be going into a group facility’ and to imagine and move towards the much more ordinary socially-valued alternatives.

Undoubtedly, there is also a broader role for governments in increasing the supply of accessible affordable dwellings, particularly in the current national housing and rental crisis. The full implementation of the new National Construction Code (NCC) Livable Housing Design Standard will assist in achieving this outcome. But this must occur in tandem with, and not be allowed to supplant, new government investments to address the acute unmet disability housing needs across the country. Given that less than four per cent of NDIS participants currently have an SDA budget in their plan, disability housing cannot be dismissed as something that is only relevant within the Scheme. It is essential that mainstream housing policies also address this shortfall, including through the proposed Housing Australia Future Fund (HAFF).

Conclusion

Housing is critical to the life chances of all Australians. To have a safe, secure, comfortable place to call home is a key foundation of ordinary daily life and strongly influences the types of opportunities we can access and relationships we can build. The NDIS, and the home and living support providers funded through it, have a critical responsibility to ensure participants choose where and with whom they live, as well as how they access daily living supports. The fundamental context for this responsibility must be to ensure NDIS funds, which should properly be seen as investment in participants, do not lead to the continuation of facilities or institutional practices, but instead to the creation of an authentic sense of home for each participant, on the same basis as non-disabled Australians.

Endnote

Usually, calls for a new approach to replace forced congregate living in group houses are met with two predictable responses: ‘What’s the alternative?’ and ‘How much would it cost?’. Neither refrain has a sound basis in reality. There is an array of alternatives to suit individual needs and choices; just as there is in the housing market generally. This has been evident for a long time. We do not advocate for a single prescribed option; that too would be inconsistent with the Scheme values of individual choice and control. Instead, the NDIS should be open to the full range of reasonable alternatives, encourage genuine innovation, and take a flexible approach to how NDIS budgets can be used for housing solutions that bring an authentic sense of home. Obviously, we are not suggesting that ‘harbourside mansions’ are a reasonable request to be funded through the NDIS, but, equally, we strongly reject the argument that individual housing choices for people living with disability are somehow unreasonable or financially inefficient when this is an ordinary expectation of non-disabled Australians.

Alternative housing options do not always cost more. Indeed, there are extra costs associated with Class 3 group houses, including for fire safety requirements, that are not incurred for an ordinary residential dwelling. This is fuelling demands from some in the SDA sector to effectively declassify group houses from Class 3 facilities and pretend that they are the same as Class 1 dwellings. This not only has the potential to compromise the safety of residents living in group houses, but avoids the real issues about the character of these facilities. That character includes the presence of extensive rules, signs, safety infrastructure, recordkeeping materials, and staff areas that are not found in ordinary homes and subvert any attempts to create a sense of homeliness, belonging, or personal authority. These also represent additional NDIS-funded expenses that are not present in ordinary homes.

The question of costs should also focus our minds on what type of Scheme we want. If individual housing choices are rejected as unaffordable, then the NDIS is not a Scheme anchored to principles of individual choice and advancing the chances of Australians living with disability enjoying ordinary lives on the same basis as non-disabled Australians. It is not providing what is ‘reasonable and necessary’ to live an ordinary life. And it is not delivering what taxpayers think they are paying for. In effect, the NDIA is deciding that some people are ‘too disabled’ to deserve an authentic sense of home. This is the opposite of what was promised and inconsistent with the proclaimed Scheme values.

In the next Paper in our NDIS Review Conversation Series, we will focus on how a balance of natural and formal safeguards can provide effective protection for participants and oversight of providers.