Maximising beneficial outcomes from Positive Behaviour Support

Key points

- Positive Behaviour Support (PBS) is an evidence-based approach with much broader application than its use in the context of restrictive practices regulation

- PBS can help shift the focus from ‘managing’ behaviours at issue to the adoption of communications and actions more likely to lead to positive outcomes and a good life

- Under the NDIS currently, the use of PBS is too compliance-orientated and this is not achieving the beneficial outcomes for participants that it should

- PBS should be part of an approach that ensures restrictive practices are only used sparingly and only when a broader plan to lift a person into valued roles in community life is in place

- Often, respecting and enabling a person’s choices is all that is needed to overcome behaviours at issue

Positive Behaviour Support (PBS) is an internationally recognised evidence-based approach that can significantly improve quality of life outcomes for some people living with disability and others. In Australia, it has recently gained particular prominence in association with the National Disability Insurance Scheme’s (NDIS) regulatory framework regarding the use (and misuse) of restrictive practices for participants. Yet, this is a very narrow framing of its possible applications and benefits, such that there may be a perception that PBS only exists as a highly specialised skill set applied in the context of restrictive practices rather than one that is relevant to all everyday formal and informal disability supports. Therefore, the NDIS may be inadvertently turning a person-centred practice into an overly compliance-centred approach to the detriment of maximising beneficial outcomes for participants. Some participants are currently receiving individual funding and referrals for specialist PBS they may not need due to compliance requirements while others who could benefit greatly are missing out.

This, of course, is not to suggest that addressing the prevalence of restrictive practices is not an objective; just that this is not the full story. In 2014, Australia’s disability ministers committed to reducing and eliminating the use of restrictive practices in disability services in order to ‘protect the rights, freedoms, and inherent dignity’ of people living with disability. The ‘National Framework for Reducing and Eliminating the Use of Restrictive Practices in the Disability Service Sector’ identified PBS approaches and the development and implementation of individual behaviour support plans as key strategies to achieve this goal. Initially, existing state and territory mechanisms were supposed to drive change, with a new model to be established under the full roll out of the NDIS. That model now sits under the NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission (NDIS Commission). To date, it seems the NDIS Commission’s most significant achievement has been to increase the reporting of the unauthorised use of restrictive practices, which is welcome, but its other efforts also need to have impact to meet the commitment to reduce and ultimately eliminate their use. In fact, data indicates that reported instances of unauthorised restrictive practice use increased from less than 290,000 in 2019-20 to more than 1.4 million in 2021-22.[1]

In this twelfth paper in our NDIS Review Conversation Series, we unpack the behaviours at issue, the ‘management’ orientated approach of implementing restrictive practices, and the consequences this has for the rights, dignity, and life chances of those who are subject to them. We consider how PBS approaches can help shift this focus from ‘management’ of behaviours at issue to assisting the person to adopt communications and actions that are more likely to lead to beneficial outcomes and a good life. To underpin this change, we identify several features the NDIS should adopt regarding how PBS is applied within the Scheme. Notwithstanding this, we emphasise the importance of respecting and enacting a participant’s choice and control, a simple foundation of supporting a person living with disability that can often negate behaviours at issue without the need for PBS or, indeed, any use of restrictive practices.

The behaviours at issue

The terms ‘behaviours of concern’, ‘challenging behaviours’, or ‘protest behaviours’ are often bandied around without any explanation of what they are or why they occur. In our Citizenhood model[2], we talk about how a person finds belonging, meaning, and fulfillment in life through taking up a range of roles that bring the person into valued social and economic connection with others. Such roles include family member, partner, friend, worker, club member, neighbour, dog walker, and so on. Some people have ways of communicating or doing that make it harder for them to take up these roles. These are the behaviours at issue, and they typically involve communications or actions that are troubling to others, particularly if there is a possibility of a person harming themselves or someone else, be that intentionally or not, or damaging property.

These behaviours are often not well understood by others, therefore they become the focus of formal service responses. When this happens, the daily character of the service is less likely to be centred on lifting the person into valued roles in community life and more likely to focus on ‘managing’ the ‘problem’ so there are less instances of harm or damage. As a consequence of this, and of the way supports are then arranged and provided, the person can become known for these behaviours and little else. Their Personhood can become diminished in the views of others and their identity reduced to a set of ‘problem behaviours’ to be managed. Often, little or no progress is then achieved in advancing the person into ordinary valued roles in community life.

Use of restrictive practices

When the focus of the service response is on ‘managing problem behaviours’, opportunities to advance the person into valued roles are likely to be lost. In managing down the risk of harm or damage, a service provider (and sometimes family members or others involved in a person’s life) might use practices that involve restricting a person in some way. These are known as ‘restrictive practices’ and might include:

- Chemical restraints – such as administering medication to sedate a person or dull their senses

- Environmental restraints – such as preventing a person’s free access to all parts of their environment or to items or activities, for example locking a fridge

- Mechanical restraints – such as using restraints to prevent or subdue movement, for example applying wrist straps to a person using a wheelchair

- Physical restraints – such as using force to hold someone down

- Seclusion – such as confining a person to a room they cannot exit by themselves[3]

Restrictive practices are problematic for several reasons. Firstly, withdrawing a person’s liberty or choice is a serious matter. The right to make decisions, and freedom of choice and movement, are fundamental expectations in our society, and these are lost when restrictive practices are applied. This loss causes harm.

Second, this harm is exacerbated by the compounding impacts of repeated use and can produce the opposite outcome to that intended. When restrictive practices are applied, they can increase the chances the behaviour at issue will continue and with similar, if not greater, frequency than before.

Third, the trauma of being restricted in some way can also escalate to new behaviours due to these traumatising experiences. Behaviours at issue and the implementation of restrictive practices in response can become a persistent ever-exacerbating cycle without any prospect of change.

Fourth, there is a fine line between implementing a restrictive practice in the name of safety and doing so simply for convenience. We have encountered many instances of the latter. Insufficient resourcing, staff shortages, time constraints, untrained staff, reliance on entrenched but misguided ‘standard practice’ routines, workplace cultures of acceptance or indifference, extreme risk adversity, and other inadequacies in care, are all factors that can drive inappropriate use of restrictive practices.

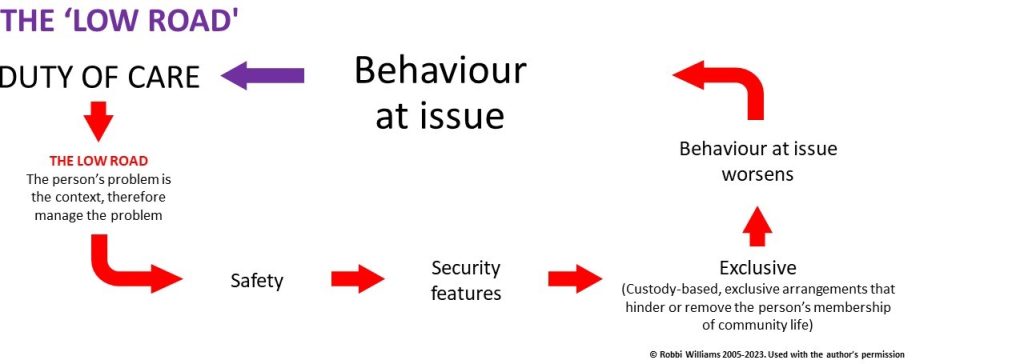

Finally, there is little doubt that restrictive practices by their nature stop a person from building their social and economic participation; a core objective of the NDIS as discussed in the eighth paper in this Series. We refer to approaches where a duty of care translates into ‘managing problem behaviours’ as the ‘low road’. As we described in a previous paper, it results in safety measures that carry security features, the consequences of which include the person being excluded from opportunities and membership of community life. Below, we return to our earlier illustration to show the ‘low road’.

Positive Behaviour Support (PBS)

One of the general themes in psychology is the relationship between a person’s actions and the consequences of those actions. This field of enquiry includes considering how people’s behaviour can be influenced by rewards or punishments for their actions, so that wanted behaviour is encouraged, and unwanted behaviour is discouraged. For example, a traffic fine is a punishment for speeding. The avoidance of a fine is a reward for obeying the speed limit. Likewise, a child learning to play cooperatively with others is rewarded by the companionship it brings and the combined approach to imaginative play that results.

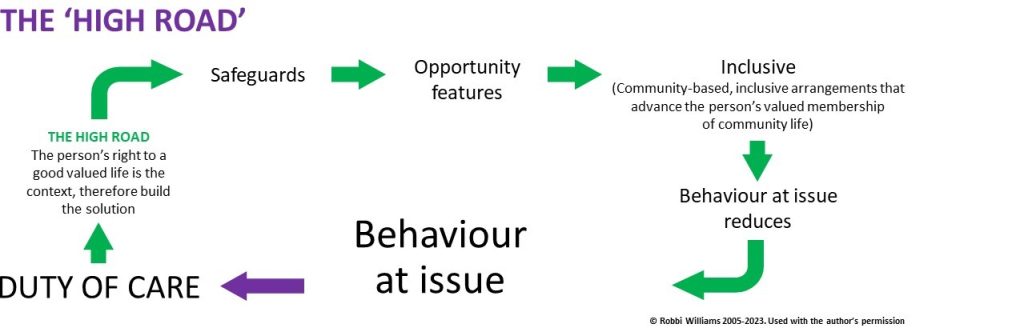

PBS applies methodologies that assist a person to take helpful actions towards a good life. As stated above, this approach goes well beyond situations where a person is at risk of having restrictive practices imposed, but it is linked with this because it can focus on supporting someone to adopt new behaviours without the use of techniques involving restriction or punishment. It is anchored on the defence of a person’s dignity and rights, on creating a positive environment, and redirecting the person to communications and actions more likely to assist them to take up what we term Personhood and Citizenhood. We call this the ‘high road’, where the duty of care focus is on advancing the person’s right to a fair go at a good life. This leads to safeguards, including involving the person in decision-making and supporting the person to adopt actions and habits that open opportunities for taking up valued roles in community life. This is summarised below, again building on the same illustration referred to above.

Among other benefits, PBS helps shift the use of restrictive practices from a default first response to an option of last resort. It helps ensure any decisions about the use of restrictive practices are based on individual needs, genuine proportional risk assessments, and the provision of good practice support.

Key to this is understanding the reasons for the behaviour at issue. All behaviour is motivated by something; behaviours do not just appear from nothing. Reasons may include boredom, anger, sadness, hunger, quest for human contact, recognition, or response to previous trauma, including trauma from restrictive practices.

Once the reasons for the behaviour at issue have been understood, it is then possible to look at how the person is supported to fulfill those needs in different ways that also lift them into opportunities for social and economic participation and the meaning and belonging that comes with this. This requires holding true to the vision that the person can move on from these behaviours and is not destined to always be known for them. This demands advocacy from everyone involved, as well as consistency and persistence of effort.

The NDIS and PBS

Given its role in providing individual budgets to participants for formal supports, the National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA) has a key role to play in advancing PBS. Additionally, the NDIS Commission is charged with regulatory functions that are central to how PBS is implemented for NDIS participants. However, there are problems.

First, there are issues with how restrictive practices are understood and used. Providers and workers have varying levels of knowledge about restrictive practices resulting in many practices being regarded as routine and legitimate when in fact they are restrictive and cause harm, including subtle (but definite) harm to the person every day. Further, restrictive practices should only be used as a last resort – or, in our view, only as an emergency measure. However, the NDIS legislation and Rules are not strong enough in this regard, or, at least, do not seem to be having the required impact to achieve this outcome. While the phrase ‘risk of harm’ is not directly accompanied by an indication of the extent of that risk, for example ‘substantial risk of harm’, the Rules do require a regulated restrictive practice to ‘be in proportion to the potential negative consequence or risk of harm’.[3] Yet, it appears restrictive practices are often used in cases where the risk is small, or, in some cases, entirely insignificant. This results in unnecessary and inappropriate loss of dignity and rights for the person and increased costs and compliance activities for the Scheme.

Second, using a mechanism like a Behaviour Support Plan to approve restrictive practices inevitably leads providers to approach this in ways that are principally about securing approval rather than improving the participant’s quality of life. Often, participants are referred to this formal process before anything else has even been tried to avoid the use of restrictive practices – utilising basic PBS tools should not require a Plan, which inevitably delays action. In essence, the process becomes a checklist and any attention to broader context and life chances is lost. For example, there is a requirement that the disability service provider consult the person about a proposed restrictive practice in their support arrangements. However, according to a recent audit, only a third of Behaviour Support Plans provide evidence this has been done.[4] Indeed, the quality of these Plans overall is currently very poor, with 80 per cent of Plans evaluated in the audit scored as underdeveloped or weak.[4] Additionally, too few billable hours appear to be used to directly engage with a participant while too many are spent on reports and compliance requirements.

Similarly, the focus on compliance is likely driving the production of overly lengthy and technical assessments to support the application. This may be diverting effort and investment away from a focus on implementing a proactive plan that lifts the person into good outcomes. A provider seeking approval for restrictive practice effectively has up to one year to find a behaviour support practitioner and implement the subsequent plan developed.[5] This is too long and potentially consigns a participant to a further year of lost life chances. Given the nature of restrictive practices, it is imperative there be a greater sense of urgency.

Third, the NDIS pricing arrangements include a single Line Item for ‘Specialist Behavioural Intervention Support’, which may be creating a ‘vanilla’ market that remains underdeveloped. People’s circumstances and needs differ greatly and require more varied and nuanced approaches. Additionally, this does not account for the different level of skills and experience among practitioners, nor the need for different skill sets whereby, inevitably, some services should be lower priced compared to others that cost more. Further, the price limit for this Line Item is among the highest hourly rates in the NDIS Support Catalogue, yet it is clear neither the quality of this support, nor its outcomes, currently reflect this significant investment.

Fourth, there does not appear to be clear national practice standards, nor the practitioner training that would lead to consistent application of such standards. There are no minimum qualifications or credentials to register as a behaviour support practitioner. This means that among the 5376 practitioners[6] currently considered suitable to deliver PBS services, there are likely to be some who are much less able to make real impact, which wastes a participant’s time and budget, and may in some cases even be harmful. There have also been anecdotal reports of practitioners discontinuing their services for participants considered ‘more difficult’ and instead taking on ‘easier’ cases. Aside from the ethical issues this raises, it erodes a participant’s budget without producing any outcomes.

As a final reflection in this section, there are inconsistencies in the NDIS regarding the importance of a vision of the possibility of change in behaviour toward better life chances. For example, in the Specialist Disability Accommodation (SDA) framework, there is a housing classification termed ‘Robust’ that relates to housing development for people with behaviours at issue. This typically involves practical reinforcement features in the property design so it can better withstand damage from the person or reduce the risk of harm to the person and others. The problem with this is that SDA developments are intended to provide long-term housing solutions for the occupants. Therefore, even though this may be unintended, the message underpinning the current approach to SDA ‘Robust’ housing is that the occupants will need those robust features for many years to come. As such, this sets an expectation the person is not capable of changing, and this assumption will likely leech into the support arrangements for this person.

Building a stronger NDIS in relation to PBS

Drawing on the points made in the previous sections, we suggest the post-Review NDIS approach to PBS might include a number of features. First, the legislation and Rules that govern the NDIS should be updated to emphasise more strongly that restrictive practices should only be used sparingly, in the presence of substantial and imminent risk, and, even then, only as a last resort, and in a way that is proportional to the nature of the risk. Some might argue that the legislation and Rules already do this, but, given the reality of participants’ experiences, this requirement does not seem to be conveyed as clearly and strongly as it should be.

Second, no restrictive practices should be authorised in the absence of a broader plan to advance the person into ordinary life chances and valued membership of community life. Importantly, this plan is broader than the current Behaviour Support Plan. This would require the service provider to build, deliver, and be accountable for the outcomes of a plan to lift the person into valued roles in community life, and in a way that safeguards that person’s dignity and rights. This means that in order to achieve compliance, the service provider would need to be authentically committed to delivering ‘transformational’ outcomes for the person. It would also mean PBS is a core part of internal practice within a provider’s day-to-day operations and not something that is only sourced from external practitioners in a time-limited manner. This would create a significant shift in provider practice and allow ‘Specialist Behaviour Intervention Support’ to be a genuinely high-quality specialist field for practitioners with qualifications, substantial experience, and broad expertise who would be available to assist the person, their family, and providers, in more complex situations, and assist PBS practice development.

Third, the NDIS pricing arrangements need to better reflect the different types of PBS support that can be helpful for participants, and to price these accordingly. This should reflect the diversity in practitioner skills and experience, allow for both support provider and specialist practitioner services, and more clearly recognise that PBS approaches have value beyond the context of restrictive practices. For example, a person experiencing a period of profound inactivity and absence of motivation may not be subject to restrictive practices but may benefit greatly from support anchored on PBS approaches.

Fourth, the NDIS will be greatly assisted by the establishment of a national curriculum for PBS qualifications and minimum credentials for registration of specialist behaviour support practitioners. A national curriculum with core common content could be delivered via a range of educational institutions, and with the goal of building a more capable and consistent specialist practitioner sector. Alongside this, all training related to disability support should include modules on human rights, support for decision making, and PBS, at a depth sufficient to then hold every worker in the disability support industry accountable for practice that upholds a person’s rights and dignity. For specialist practitioners, there needs to be a mandatory requirement to undertake continuing professional development. We also recommend the development of a community-of-practice with functional links to the NDIS where PBS tools and techniques can be curated to shape industry practice and to help inform the NDIA about how it might evolve its commissioning in relation to behaviour support over time.

Fifth, the Scheme needs to assert greater urgency on providers where approval is being sought for restrictive practices. Any such approval should only be given for a shorter period of time, and with the expectation the provider moves much faster (we suggest three months as a maximum, and only for participants in the most complex circumstances) to establish a proactive plan to move the person away from restrictive practices and towards ordinary life chances.

When the issue is about denial of control and choice

Having charted the above narrative, we cannot close this paper without noting that it is entirely possible a person’s behaviours at issue – usually termed ‘behaviours of concern’ in the provider setting – are a result of their frustration at having their choice and control denied. In our work undertaking social audits of disability services, we have seen examples where people have had restrictive practices imposed on them because, for example, their behaviour is in protest at having to live in a shared house with people they do not wish to live with. As such, the remedy is not the installation of a Behaviour Support Plan to support the person to adopt and adapt more helpful habits and actions. Rather, it is that the provider, NDIS, and informal supporters involved in the person’s life need to stop and listen, and to find a way to facilitate the person’s choice.

In this way, the problem is not a ‘behaviour of concern’, but a ‘service of concern’. Here, the remedy might include an independent party such as an intermediary (see our previous paper on this topic) spends time with the person to understand their preferences and how these might be met. This raises the question of how best to ensure disability services and their staff can best help to lift participants into valued roles in community life, anchored on the person’s dignity and choice. This is the subject of our next paper in this Series.

Conclusion

PBS has much to offer the NDIS and its participants. However, it is currently framed and implemented in an overly compliance-orientated manner that risks constraining its potential positive impacts in upholding and defending the rights and dignity of people living with disability and advancing their life chances. A fuller application of PBS in the context of broader plans to lift people into valued roles in community life is needed if we are to maximise the benefits of PBS under the NDIS. It is critically important the NDIS and all its stakeholders hold true to a vision of the possibility of change toward better life chances for every participant, regardless of the perceived ‘drama’ of a participant’s current situation.

Footnotes

[2] R. Williams, ‘The Model Of Citizenhood Support’, 2nd edition, 2013

[3] For further information, see ‘National Disability Insurance Scheme (Restrictive Practices and Behaviour Support) Rules 2018’, Section 6 and section 21

[5] Under Section 13 of the Rules, the provider has up to six months to engage a practitioner, then, under Section 19, the practitioner has up to six months after being engaged to develop the Plan. ‘National Disability Insurance Scheme (Restrictive Practices and Behaviour Support) Rules 2018’, Section 6