Rethinking NDIS assessment tools to drive simplicity and equity

Key points

Purpose of an assessment

- To determine if a person is eligible

- To ensure the response offered matches a person’s needs and is reasonable

- To confirm that the response is equitable when compared to others in the Scheme

Components of an assessment

- Assess nature of disability to determine if a person is eligible for the Scheme

- Assess consequences of disability to determine a draft overall budget that is reasonable for a person’s needs, and which can be understood in terms of transactional and transformational benefits, and which is equitable compared to other participants

Characteristics of an assessment tool

- Simple, accessible, respectful, and holistic

- Not focused on deficits and absences

The issue of assessments in the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) has a storied – and controversial – past. Most people in the disability community associate the topic with the National Disability Insurance Agency’s (NDIA) ill-fated foray into establishing ‘independent assessments,’ later abandoned in 2021, although not before leaving many with deep concerns and distrust of both the Agency and politicians. Yet, unless each person is to receive exactly the same plan and budgets, it is inescapable that an ‘assessment’ of some sort for each participant must occur – and, indeed, has been occurring ever since the Scheme began. Therefore, the key question is not if, but rather, how assessments are used in the Scheme.

Eligible | Reasonable | Equitable

The purposes of an assessment for the NDIS should be to determine if a person is eligible; ensure the response offered matches a person’s needs and is reasonable; and confirm that the response is fair and equitable when compared to others in the Scheme. The assessment process should be as simple as it can be to fulfill this purpose, fully accessible to the diverse range of participants, dignified, respectful, holistic, and efficient while still allowing an appropriate level of flexibility and adaptability to a person’s context. It should use as few questions as is necessary to produce a clear understanding of the consequences of disability for a person and result in a draft budget – that is, an overall budget signal, not a guaranteed amount – that is the reasonable and necessary cost of sustaining, or lifting, a participant into authentic valued roles in mainstream community life.

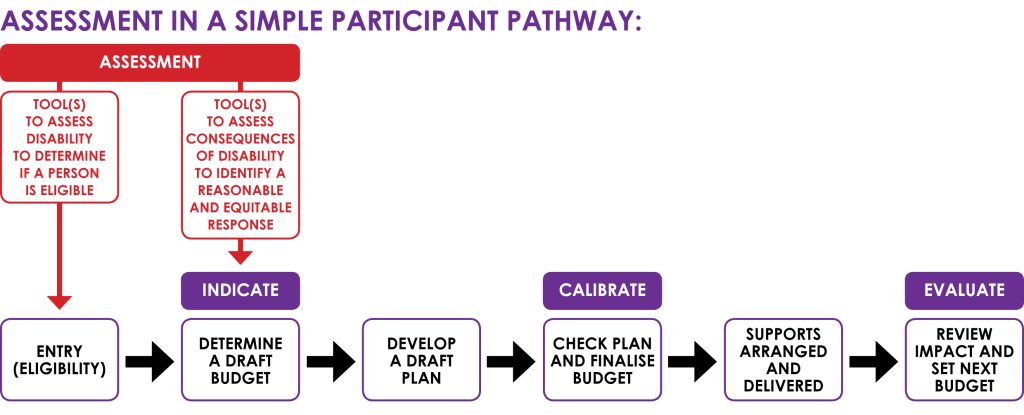

As described in our first two papers in this NDIS Review Conversation Series, this assessment should occur as part of a simple participant pathway. Once a draft overall budget is indicated to a participant, that person can use this as a guide to create a plan in accordance with their individually defined goals based on the amount of funding likely to be available. They then move through the simple participant pathway where the Plan is calibrated and later evaluated, as we have previously described. The components of the evaluation should be closely aligned with the assessment tool so that the impacts of the plan investments are clearly measured. Given the content of a participant’s Plan is articulated by the participant, the supports it enables are more likely to be tailored to the individual, have a strong impact on the person’s life, and increase the likelihood of the NDIS producing genuinely impactful benefits for Australians living with disability.

Avoiding a repeat of past mistakes

We acknowledge that assessments in the NDIS present many challenges, which are compounded by the issue of how to best determine what is ‘reasonable and necessary’. However, the NDIA has also shown a problematic preference for assessment tools that are overly complex and predominately clinical in nature. Any assessment tool that requires a health professional to implement is not a good fit for the NDIS. It is also very unlikely to be focused on the consequences of disability for a person within the context of their individual life, which is what the NDIS is supposed to be directed toward. Gathering clinical data is also costly and time consuming, making an overwhelmingly clinical approach more inefficient.

The NDIA’s attempt to establish ‘independent assessments’ as a core part of the access, planning, and review pathways for the NDIS reflected this focus on clinical measures and skewed too far toward the ‘medical model’ of disability. A number of standardised clinical assessment tools were selected for use despite the fact they were not designed for the purpose of setting individualised plan budgets and included questions of little or no relevance to the NDIS context. Non-clinical aspects of a participant’s situation, such as their goals and priorities for funded support, were largely overlooked. The time required to complete the assessments was said to be about three hours – although during the second pilot phase they took on average longer than that.ii The NDIA also compromised stakeholder confidence in the legitimacy of the pilot phase by starting to contract providers while the trial was still underway and had not yet been properly evaluated.

Despite abandoning the proposed ‘independent assessment’ process, the NDIA continues to use standardised clinical tools in its determination of budgets. For example, children and teenagers typically undergo a Pedi-CAT (Paediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory – Computer Adaptive Test) assessment while adults usually complete the WHODAS 2.0 (World Health Organisation Disability Assessment Schedule). Both are clinical instruments that largely focus on deficits and absences while providing only a rudimentary picture of a person’s daily life and life chances. This approach also creates perverse incentives for health professionals to over-diagnose and/or exaggerate deficits for the purpose of accessing the NDIS. This is symptomatic of an approach that is not fit-for-purpose in its current form.

The NDIA is now undertaking an Information Gathering for Access and Planning (IGAP) project to design a new assessment model and can be credited with taking a more robust codesign approach to this compared to ‘independent assessments’. The NDIS Review will also consider this topic. Both these processes should aim for simplicity using the aforementioned elements of ‘Eligible, Reasonable, Equitable’.

A simple assessment tool

The first component of a simple assessment tool should be to establish if a person is eligible. As the NDIS is designed for people living with significant and enduring disability this is the aspect of an assessment that will be clinical in nature. The necessary information is likely to be available from clinical professionals already known to the person. As such, the assessment for the purpose of determining eligibility is focused on measuring disability.

The second, more substantial, component of a simple assessment tool should focus on understanding the impact of a person’s disability on their daily life and their life chances in order to establish a draft overall budget signal that is reasonable. The simple assessment tool does not need a multitude of questions about each aspect of a person’s daily life when in each case only one or two might be sufficient. For example, questions about the amount of assistance a person needs to get out of bed, use the bathroom, get dressed, prepare a meal, clean a surface, and so on will likely produce quite similar responses so repetition seems unnecessary.

To assess life chances, the tool would seek information about items such as the suitability and sustainability of the person’s housing situation, their current employment or access to education and training, the range of social connections and relationships a person has in their life, the level of support they need to understand options and make decisions, and, most tellingly, the overall number of ordinary valued roles the person has.

The primary source of information in the second component of an assessment should be the participant and, where involved, likely their family and allies. It would be person-centred, not clinical, in nature. Therefore, the assessment for the purpose of establishing a draft budget signal is focused on measuring the consequences of disability, including the consequences of how our society and economy typically react to disability. Given the size of the NDIS, it is feasible – and optimal – that the NDIA codesigns its own bespoke assessment tool to fulfill its specific purposes rather than relying on existing standardised clinical assessment instruments. Once codesigned, a simple methodology using a sample of current NDIS participants with budgets that are a reasonable match to their circumstances should be used to cross-test and calibrate the assessment tool.

This instrument would also help identify those consequences that relate to the lack of accessibility or inclusion of other government and community services, programs, facilities, and resources so representation can be made to the responsible body about urgently addressing those problems rather than the NDIS bearing all the financial consequences of an inaccessible, non-inclusive society.

Transactional and transformational benefits

There are two main types of consequences of disability and, therefore, two main types of corresponding benefits. First, as described above, the impact on daily life can mean a person needs practical assistance to navigate their daily life. The results of the assessment should contribute to a draft budget signal for those funded supports intended to deliver the corresponding transactional benefits; that is, practical supports for daily living that will likely be needed repeatedly into the future.

Second, the impact on life chances can mean a person has far less opportunity than a non-disabled person to take up mainstream waged employment, access education, find a place to genuinely call home, establish a rich array of connections and relationship, and so on. The results of the assessment should contribute to a draft budget signal for those funded supports designed to deliver transformational benefits to a person’s life chances; that is, funded supports to achieve a person’s individually defined goals and fulfill their potential as an active valued member of mainstream community life. These benefits can also include authentic capacity-building outcomes, where a person is assisted to gain skills and knowledge, or investments in assistive technologies, that enable independence; both of which can reduce the future need for transactional benefits. These benefits should create permanent positive change and, therefore, a participant’s budget for funded supports to increase their life chances should reduce over time as goals are achieved and sustained. For example, technology that enables a person to open and close doors and operate appliances through voice control facilitate greater independence and can reduce the need for hands-on assistance from a paid worker. Similarly, a motorised wheelchair or a vehicle modification could assist a person to travel independently to appointments or employment and reduce their need for transport assistance. Because of these possibilities, narratives that imply all budget reductions in NDIS plans represent unfair cuts are not accurate.

The varied nature of the impact of disability on daily life and on life chances means that it is possible that two people with similar types or degrees of disability may receive different budgets. One person already living with a full array of life chances available to them may only need funded supports for transactional benefits, while another may need extensive transformational benefits to change their circumstances of, for example, unemployment, homelessness, or loneliness.

Fair and equitable outcomes

Currently, there are significant inconsistencies in the budgets approved for participants with similar consequences of disability. This can be the result of a lack of calibration between the judgements of different NDIA staff or due to the varying capacity of individuals and/or families or supporters to advocate for their needs and assert their goals. For the NDIS, this likely means some participants receive less funding than they need while others get more than they reasonably need. The reputations of the NDIS and the NDIA are compromised due to both real and perceived unfairness, while additional inflationary pressures are placed on the overall cost of the Scheme. To reduce these cost pressures, elements in plans are often arbitrarily cut as part of the sign-off process, without necessarily reflecting a participant’s priorities for funded support. That is not a coherent or sustainable solution to this difficult problem.

The utilisation of a simple well-tested bespoke NDIS assessment tool should assist in calibrating the decisions of NDIA staff and ensure each participant’s NDIS budget is fair and equitable when compared to those of more than half a million other NDIS participants. This should mean that the draft budget signal produced by the assessment is both reasonable for the participant’s needs, and equitable in relation to other participants. Notably, other jurisdictions have previously applied this type of approach, such as local authorities in the United Kingdom through their Resource Allocation System (RAS) for individualised funding, and appear to have had far fewer issues compared to the current NDIS arrangements (unfortunately, it is more difficult to see those arrangements in the Untied Kingdom now, because many of those arrangements were scaled back as a result of austerity measures following the 2008 global financial crisis). In many respects, a RAS is a key tool when thinking about the NDIS as a social insurance scheme.

No assessment tool, whether it is specifically designed for the NDIS or a standardised clinical tool, can ever be expected to produce perfect results. So, alongside the ability to respectfully engage with participants to test and verify the nature of their circumstances, there is a need for sound human judgement and for this to be well-calibrated across agency staff. Therefore, in addition to building a RAS, the NDIA should invest in building staff capacity as budget-setters and evaluators (not as planners because, as per our second paper in this Series, we see that role lying outside the Agency). To assist this, the NDIA would need to invest in building a ‘body of knowledge’ accessible to all staff. This would comprise composite wisdom and insights from identified good practice among staff, plus insights from the review (evaluation) of a person’s budget arrangements to identify what types of investment work better than others at sustaining, or lifting, a person into ordinary life chances.

To conclude, we believe that a simple bespoke assessment process, based on the elements of eligible, reasonable, and equitable and implemented as part of a simple participant pathway, would strengthen the Scheme. The current NDIS Review presents a good opportunity to set aside the NDIA’s past missteps in relation to ‘independent assessments’ and look to how assessment tools can be used in the NDIS for the benefit of participants and the future of the Scheme. Ensuring that each participant receives the funded supports needed to reasonably deliver the transactional and transformational benefits that will lift or sustain them in ordinary life chances, characterised by a rich range of socially valued roles and relationships, and in a manner that is fair and equitable to all, will underpin an effective and sustainable NDIS that delivers on its promise.

In the next Paper in our NDIS Review Conversation Series, we will focus on raising the bar for what constitutes authentic connection and participation to ensure that NDIS participants are being welcomed and included as valued members of their local communities.