Unlocking genuine grassroots connections is key to LAC success

Key points

Current situation

- Largescale commissioning of LAC providers means strong local roots, knowledge, and networks are usually absent

- Participants do not have choice of LAC

- LAC role is conflicted between serving the person and serving the Agency

What needs to change

- Engage grassroots LACs to unlock genuine local knowledge and connections within local communities

- Place participant choice at core of LAC model

- Focus on development and continuity of relationships, where the LAC is the agent of the person not the Scheme

- Co-design a new LAC model and implement a pilot program to gather data about

The role of Local Area Coordinators (LACs) under the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) is pivotal to realising the promise of advancing the life chances of Australians living with disability. Emerging in Western Australia in the late 1980s, along with broadly comparable initiatives elsewhere, the LAC approach was designed to focus on facilitating connections between people, families, local communities, services, and government supports. It originated as a role that would create long-term relationships of trust and respect that could enable individuals to pursue their personally defined life goals and fulfil their potential. It was also intended to build the capacity of communities to be places of welcome and inclusion where each person is an active, contributing, and valued member of community life. In 2011, the Productivity Commission’s report on Disability Care and Support identified the LAC role as key to the success of a new national disability scheme.

Unfortunately, the implementation of the LAC role has lacked the clarity of purpose and practice needed to ground the Scheme within the local context of each participant. LACs undertake Scheme enrolment and related functions that sit more appropriately in the realm of National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA) staff. The LAC role is conflicted between serving the person and serving the Agency, with little to no focus on community connection. This has added considerable time and resource burdens and distracts from the beneficial elements of the original role. LACs spend most of their time connecting people to the NDIS rather than to their local community and mainstream services. NDIS participants regularly tell us their LAC has limited knowledge of – or presence in – their local community.

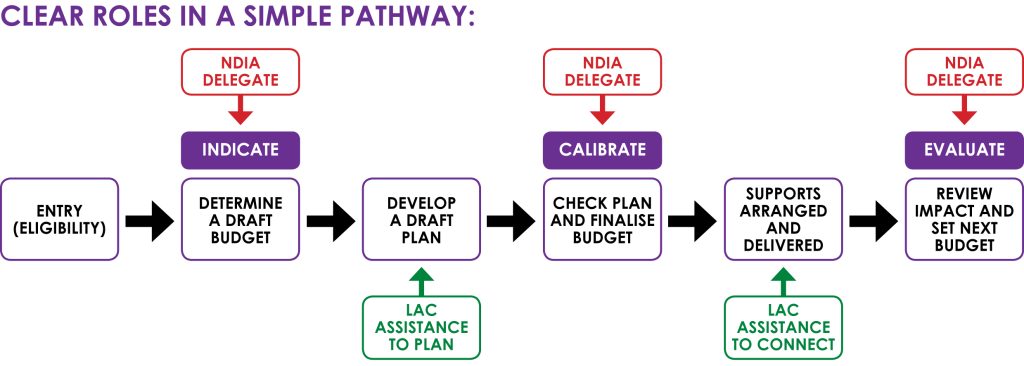

In the first Paper in this NDIS Review Conversation Series, we described the need to restore simplicity to the NDIS participant pathway. In this second Paper, we address how a reformed LAC model plays an important part in that pathway and helps maximise the promised transformational benefits of the NDIS for people living with disability. For this to happen, the LAC role needs to refocus on unlocking genuine grassroots connections in local communities, linking people to opportunities and both formal and informal supports, within the context of authentic inclusion.

Harnessing grassroots knowledge and local connections

A participant’s plan encompasses what they wish to prioritise and act upon. It is likely to include both formal elements (things the NDIS can fund) and informal elements (resources and opportunities in local community life that are unlikely to need NDIS funding to make them happen). For both, longstanding local knowledge and networks are key. This means the LAC role is inherently local. Grassroots organisations and agencies hold the greatest prospects of delivering the best outcomes because they are embedded in the local communities they serve. They know who to talk to about what, and the most promising entry points for connecting to community life. They are of the communities that they serve.

This was recognised in the Productivity Commission’s description of the LAC role as involving “locally based staff, operating at a ‘grassroots’ level” (p.411). Further:

“Local area coordinators would be based in, and have close connections to, the local community, with knowledge of local providers and NGOs, and with some scope to respond flexibly to people’s needs. While the Commission sees the scheme as being based on national standards and funding, it would be locally executed, with power over such features as service delivery and capacity building at the local level. The NDIA should be about local solutions to local circumstances.” (p.446)

The current largescale commissioning of LAC providers does not achieve the objective of harnessing grassroots resources and realising positive outcomes at a community level. For example, in South Australia LAC supports are provided by three agencies, each serving vast geographic areas of the state encompassing many different local communities. It is highly unlikely that such agencies have the degree of local roots, knowledge,and networks necessary to provide effective LAC supports in every community they cover. Indeed, to date they have not demonstrated any advantages over what would be expected from networks of smaller, community-embedded grassroots agencies.

It is hard to imagine significant improvement if the NDIA itself were to take on the LAC role, as has been proposed by some advocates and, indeed, by the Productivity Commission back in 2011. The only way to improve the current largescale commissioning approach would be to recruit LACs from within local communities. However, these people are likely to be drawn from existing local grassroots organisations, which, in effect, would result in an unfortunate form of community asset-stripping by vacuuming up local staff into largescale agency work.

While there are additional challenges in providing LAC supports in remote areas with ‘thin markets’, a developmental approach to commissioning programs offers a pathway to an effective solution. This would see the NDIA partnering with local communities and local leaders to co-design and co-produce appropriate local solutions. We believe this approach would be essential in First Nations communities.

Focusing on ongoing relationships

The LAC role should be anchored on the development and continuity of relationships. Participants regularly tell us that their allocated LAC changes frequently and that their interaction with them is minimal. It is critical there be strong ongoing relationships between:

- The LAC and the participant so trust and insight are built and sustained

- The LAC and the local community they are embedded in, so a shared history and depth of knowledge are built and sustained

The current largescale approach to commissioning LAC providers does not support this.

Similarly, as identified in our first Paper, the LAC role is currently conflicted between the dual functions of serving the Scheme and supporting the person. This conflict undermines the relationship and trust between the LAC and the participant. It can be resolved by clearly distinguishing between the role of the NDIA delegate as the agent of the Scheme, and the role of the LAC as the agent of the participant.

The core components of the LAC role would be to support participants (who choose to access LAC assistance) to articulate their priorities and plan the actions they would like to take. Depending on the participant’s circumstances, the LAC might then assist with connections to local community resources and opportunities that bring the participant into active valued membership of local community life. Importantly, the LAC could also assist the participant to understand how to navigate agencies. As was described by the Productivity Commission, “[LACs] should be able to lay a clear pathway for clients to acquire the support they need. This includes through the NDIS itself, as well as advising clients on supports available through other government agencies” (p.485). These roles require a focus on developing long-term relationships of trust with participants, therefore the LAC model should be underpinned by participant choice.

Embedding participant choice

‘Choice and control’ are fundamental and foundational principles of the NDIS, yet so far these have not been applied to LAC supports. Given the pivotal nature of the LAC role, it seems deeply counterintuitive that a participant is not permitted to choose or change their LAC according to their priorities and preferences. This continues to be at odds with the values that the Scheme and Agency purport to uphold. It is important the NDIS Review revisits this issue and gives particular attention to the origins of this approach, which have since been overridden.

In 2011, the Productivity Commission envisaged LACs would be employed by the NDIA and they would, among their other roles, fulfil regulatory functions under the NDIS, including in relation to participant wellbeing, provider standards, and disputes. Therefore, the Commission stated that people should not choose their LAC because this could constitute a potential conflict of interest regarding that regulatory function. However, this is not the LAC model that is operating under the NDIS, and nor should it be. A regulatory function would add additional conflicts to the role and take it further away from fulfilling the purpose of being an agent of the participant. Hence, the original basis upon which choice was said to be inappropriate for this aspect of the NDIS does not exist in the way that the NDIS has been implemented. As such, there is no valid reason why participant choice is not enshrined in the LAC model.

We believe participant choice is essential to the role of the LAC as the agent of the participant in the NDIS. A commissioning approach that allows the participant to choose their LAC should be at the core of a reformed LAC model. The model should encourage a diverse range of LAC offerings that could include, but not be limited to, locality-based grassroots agencies, agencies specialising in specific types or consequences of disability, and agencies focused on First Nations people or culturally and linguistically diverse participants. This means the participant would have the opportunity to choose the LAC that fits them best. It could be because of a deep knowledge of the person’s disability or culture, or a focus on a particular high-priority goal such as a desire to find sustainable mainstream waged employment. Participant choice would also incentivise LACs to improve the quality of what they offer so they are a provider of choice.

Rightly, an approach that embeds participant choice of LAC requires a revised funding model. One simple way to do this is to provide a baseline budget allocation to each participant seeking LAC assistance, which the participant uses to choose LAC supports. There is more we could say about this, but not in this short paper.

Tier 2 and LAC supports

In addition to the LAC service to NDIS participants, there are two further considerations. First, there needs to be local grassroots LAC support for those Australians living with disability who are not NDIS participants, primarily through information and linking services. Second, the local resources of grassroots agencies should be sustained and leveraged to build the capacity of communities to welcome and include all people living with disability as active valued members of community life.

We believe these two LAC roles could form a specific stream within a reformed Information, Linkages, and Capacity Building (ILC) program as part of what the Productivity Commission originally described as ‘Tier 2’. Rather than being paid from a plan budget for the provision of LAC support to an individual participant, these LAC roles could be funded through ILC grants to grassroots organisations and agencies embedded in local communities on a population and program basis.

‘Tier 2’ supports and ILC programs remain essential elements of a successful NDIS, as well as a critical pathway toward ending segregated service provision and developing more inclusive mainstream options. We will delve more deeply into this topic in a future Paper in this Series.

To conclude, we believe that unlocking genuine grassroots connections is the key to a successful LAC model that produces transformational benefits for Australians living with disability. It is untenable to continue the current largescale commissioning of a few LAC providers to cover vast geographical areas without offering any participant choice. We have identified some guiding principles for a reformed LAC model that we hope can be advanced by an authentic co-design process this year. A pilot program of an alternative LAC model should be implemented to gather data, finetune details, and lay the groundwork for scaling up. The roll out of a new model should then be accompanied by strong accountability and evaluation mechanisms that ensure proper measurement of impact and outcomes – something that appears underdone in the current approach. These steps would set the future of the LAC role under the NDIS on a more promising trajectory.

In the next Paper in our NDIS Review Conversation Series, we will set aside the NDIA’s past mishandling of ‘independent assessments’ to consider how other assessment tools might be utilised to ensure simplicity and equity in the Scheme.